A Tale of Two Economies: A Collaboration with Fynn Glover

Fynn Glover and I worked together at Matcha, where he was CEO. Fynn and I have always enjoyed debating topics outside of work relating to history and economics, and recently decided to collaborate on a post for his blog. I’ve cross-posted it here, and recommend everyone subscribe to his blog for similar posts about technology, history, economics, and literature.

Recently, Fynn and I both listened to an interview with Marc Andreesen. During the interview, Andreesen makes the point that since 1970, there have been two economies: growth economies and slow economies.

Here’s an excerpt from the transcript.

“All sectors of the economy aren’t the same… basically what you see is, it’s a Tale of Two Cities. There are a whole bunch of sectors, let’s call them the super fast change sectors… getting disrupted on a regular basis. These are sectors like computers and media and retail, and by the way, cars, and clothes and food, most of the stuff you buy. Those sectors basically over a 20-, 30-, 40-year period experience these really rapid price declines. The price declines and then also and/or dramatic improvements to the product. The common example might be just the television set. Then you take the other sectors. We might call those the slow sectors. There are a bunch of those, but three really big ones. Housing, healthcare and education. And those sectors exhibit the opposite behavior, the opposite behavior of your TV set. The 100-inch TV set that covers your wall is going to cost you 100 bucks. The four-year college degree is going to cost $1 million. And it’s like the four-year college degree is basically… Just think about technologically, it’s an unchanged experience from 100 years ago. Getting a degree from a college university today, it’s the same set of activities, same format, it’s teachers in the classroom, it’s written exams. There’s been no technological change whatsoever, and prices have exploded.”

On one of our recent calls, Fynn and I shared our thoughts on the interview, and as we discussed, we thought the topic was worth exploring publicly. In the remainder of this post, we explore together some of the underlying factors that lead to fast or slow growth sectors.

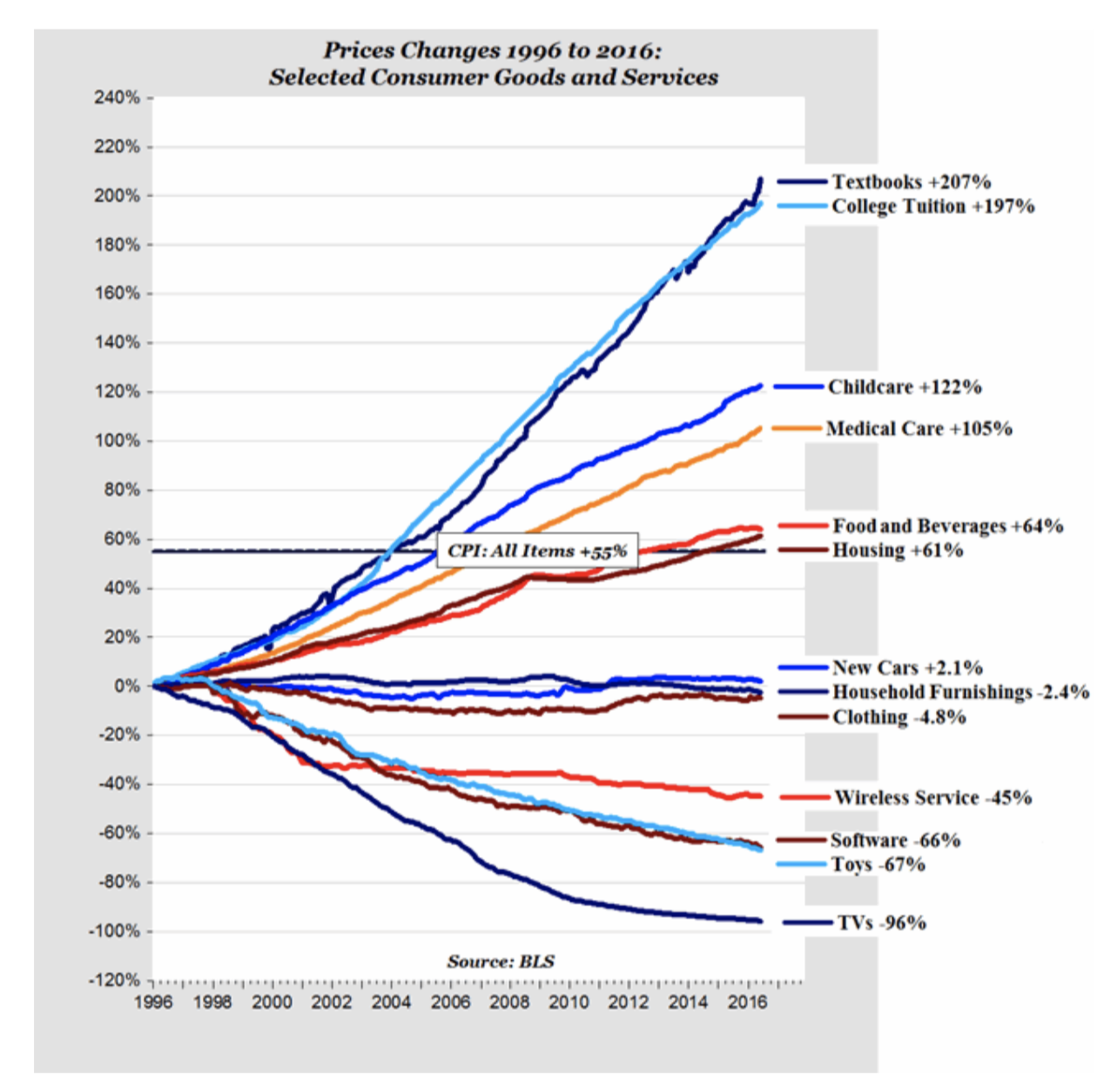

Looking at the chart below, which shows data back to 2000 (although the trends would be directionally similar if we went back to the 70s), it’s hard not to share Andreessen’s observation of a “Tale of Two Cities”. There is an immense gap between a cluster of categories that have had deflation, or basically no inflation, and a cluster of categories that have had inflation greater than the overall average (~60%).

Andreessen’s point is twofold:

- fast sectors are those that have “experienced technological disruption”

- slow sectors are those in which there has “been no technological change whatsoever,” and often those that are highly subsidized.

This narrative is easy to accept at a high-level, but it leaves out two of the most significant factors to explain why a sector may be fast or slow.

These factors are: 1. Labor costs and global trade 2. Bundled vs. unbundled sectors

Labor Cost & Global Trade <> US workers are expensive

Many of the “fast” sectors can be bucketed into a larger category of consumer goods and electronics. The relative price decline in these categories overlaps fairly cleanly with the offshoring of US manufacturing, and this is largely the explanation for the deflationary effect in these sectors.

Has there been technological impact? Certainly. But the largest cost driver for manufacturing is labor. Between 1970-2020, any sector that could produce goods outside of the US would be a “fast” sector, regardless of the influence of technology on that sector. As Carlota Perez commented on Fynn’s blog, “the maturity of the mass production revolution was stretched during this period by the historically unique phenomenon of introducing into the global economy the whole of China.”

Consumers may have some degree of preference towards goods that were produced in the USA, but ultimately their experience of a television or car is no different whether it was produced in the US, Mexico, China, or any other country, all other things being equal, so those effects on price are small. The same cannot be said of other sectors on the chart that are “slow”, like those relating to education and health care, which are the poster children for egregious price changes. These services are largely administered in person, and therefore the consumer and labor markets cannot be unbundled in this same way.

This is straightforward enough, but begs the question of why the delivery of these services hasn’t changed to become more efficient, which leads to the second factor that explains fast vs. slow.

Bundled or unbundled? Tech’s impact on slow industries appears more negligible than it is

Education is an interesting slow industry. Looking at the chart, it seems unbelievable that the price of college textbooks, for example, has increased by 150% in 20 years. While this may not completely rationalize that level of price change, it’s important to keep in mind that when one buys a college textbook, they are not just buying a book, they are buying a part of a bundle of classes, campuses, and networks.

Because we’re social creatures and school remains central to multiple forms of matchmaking, networks remain the hardest component of education to unbundle, thereby limiting the ability to reduce distribution costs, and therefore the potential for productivity growth.

Tuition is the platform fee for the core product (the education), but the whole product (to use Crossing the Chasm terms) includes a litany of features and add-ons. Just as a software application is worth more if it is part of Apple’s App Store ecosystem than if it were just floating around as a loose binary, a textbook is worth more in the context of the whole higher education product than it would be on the anonymizing shelves of a Barnes & Noble.

Has technology made it vastly cheaper to deliver educational content? Absolutely. It just appears that it hasn’t, because of a bundle that remains central to our social fabric. It’s this social fabric that is hard for software to eat; not the delivery of education itself.

The question to ask

It was Andreesen’s old friend Jim Barksdale who once opined: “there are only two ways to make money in business: bundling and unbundling”. In the slow example (education), we see an example of high pricing power being sustained by a powerful bundle offering, and in the fast example (consumer durables), we see an example of an economy unbundled in such a way to create price competitiveness by matching low wage exporters with high wage importers.

If this has been the story since the 1970s, then perhaps rather than asking ourselves how technology and software will affect productivity in the coming decades, we should ask what opportunities exist for bundling and unbundling various sectors. There are clearly such opportunities in education, but it’s less clear what will be done about the harder-to-substitute parts of the bundle. Supply chain turbulence has perhaps cast doubt on the future of the supply chain unbundling that went into overdrive along with global trade since the 1970s.

Your guess is likely better than ours - we’ll check back in another 50 years.